Art is controversial. Society has debated for years who is qualified to make what and if audiences have the palette to digest what they consume.

So let us preface this piece by saying it is not a critique of Issa Rae’s art but rather a peeling of the layers that influence her art. Over the last couple of weeks, Black social media has been infighting over the depth of Issa Rae’s portrayal of Black life, whether it be something she acted in, wrote, or produced. Quickly the discussion devolved into claims Black folks resent Issa Rae because she was not raised in poverty and how Black art is often dismissed if it comes from a Black person who was raised in comfort. The latter claim is ahistorical.

Black Americans have a long history of embracing women from upwardly mobile families becoming tastemakers and artists. Let’s look at a few.

A’Leila Walker was the daughter of Madam C.J. Walker, America’s first self-made female millionaire. She became president of her mother’s company upon her mother’s death and shared her wealth as one of the biggest patrons of the Harlem Renaissance, hosting parties where everyone from the Talented Tenth to struggling artists socialized in her homes. Her mansion Villa Lewaro was used as a headquarters for the first wave of the Civil Rights Movement and early years of the NAACP.

Eunice Johnson was the daughter of a physician and high school principal, and her maternal grandfather co-founded and served as the president of Selma University. As she helped her husband John H. Johnson build Johnson Publishing Company, she named their flagship magazine Ebony. The landmark periodical illustrated a wide spectrum of Black life, ranging from the subjugation of Jim Crow to the luxurious lives of businesspeople, athletes, and entertainers. She created the Ebony Fashion Fair, a traveling fashion show that raised millions for HBCUs. She brought couture to Black civic organizations in cities like Detroit and Washington, D.C. and rural parts of the Deep South. When cosmetics companies denied her request to make deeper shades of makeup for her models, she proceeded to start Fashion Fair, the first prestige makeup brand dedicated to Black women.

Phylicia Rashad and Debbie Allen are the daughters of an orthodontist and art curator, and both women have been entrusted for years to depict Black life. Phylicia tends to portray characters marked by their dignity, and she is still viewed as a pillar of grace by younger generations. Debbie Allen has choreographed and directed hundreds of shows that remain timeless, but perhaps her stewardship of The Cosby Show spinoff A Different World was the most impactful, helping to spur a renaissance of HBCUs. Both sisters have sponsored budding artists, with Chadwick Boseman being amongst them.

The four women mentioned had immersive, positive Black American experiences in their youth. And here is where we circle back. Issa Rae, born to a Black American mother from Louisiana and Senegalese immigrant father, has shared she grew up detached from Black American culture.

In case you might be unfamiliar with our platform, we write from an ethnic lens, not just Black generally. Black Americans are those who descend from United States chattel slavery, making us a unique ethnic group.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), children form their cultural identity around the ages of 3-4, saying “[t]his identification comes from the interactions they have with their family members, teachers, and community.” The APA goes on to say “[b]y age 7-9, children are more aware of the group dynamics around culture and race. This includes the histories of their own culture and how their culture is similar, different, or a combination of other cultures.”

Issa Rae was born in Los Angeles, but her family relocated to Senegal when she was three years old. She told the New York Times her father felt “living in Africa would also instill his children with discipline and respect for their heritage.” When the family returned to the United States, they lived in Potomac, Maryland where she said her social life was made up of “things that aren’t considered ‘black.’” In an interview with Conan O’Brien, she noted even her white peers realized she was disconnected from “mainstream” Black culture.

She had some passing interactions with Black students during middle school where she says she was criticized for “acting white,” but it was not until her enrollment at King/Drew Magnet High School of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles that she had her first immersion with Black Americans, calling it her ‘‘pinnacle black experience.” This is well past the age most Black Americans have already experienced cultural immersion.

Black American children can still have cultural immersion even if they attend predominantly white schools, but according to Issa, that was not her case. She used the entertainment she had previously seen on such as Boyz N the Hood and Moesha as a litmus test for Blackness, seemingly taking a mad scientist approach to dissecting Blackness as far back as her adolescence.

In short, her work at times feels more like exhibitionism than immersion.

Granted, she should be able to tell her stories because there are Black people like her who exist–those who were not provided up close exposure to Blackness until later in life. But we must be aware there are millions of Black Americans who do not relate to this experience and it has nothing to do with classism.

Possibly some people are jealous of Issa Rae, and of course some Black people have experienced others trying to mitigate their Blackness because they were raised in comfort. Still, it simply is not true across Black America. After all, we love fictional uppity Black girls–Whitley Gilbert, Lisa Turtle, and Hillary Banks. The pretty girls who wear the prettiest clothes who sometimes do not-so-pretty things, but we root for them nonetheless.

Issa Rae’s statement “I’m rooting for everybody Black” at the 69th Primetime Emmy Awards landed her a place in the pop culture lexicon in 2017. A couple of months later, she was quoted as saying “I don’t represent all black women. I just represent myself, and that’s all I can do.”

Quite frankly slapping “Black” on a story because the cast is melanated is haphazard in post-2000 America. The “African-American” population is far more diasporic than it was when Issa Rae first became infatuated with Black American entertainment from that golden age of the 90s. When this is pointed out, far too often people respond with “well, I’ve been called the n-word” or “the police can’t tell the difference when we get pulled over,” which are such reductive ways of defining yourself.

Perhaps Issa Rae should make more ethnic distinctions with her characters. Many Black Americans noted on TikTok that her hit show Insecure seemed to be more fitting to a Black immigrant/first-generation experience versus Black Americans who have generational equity in navigating race in America or that it appealed to those who did not come to experience Blackness until later in life. That just is not the case for most Black American viewers, though it is not to say Black Americans can’t appreciate her work despite the differences.

It is quite possible her work that centers around Black American elements will continue to have an exhibitionist quality because she did not have the immersion during the key formative ages. It is not an insult but rather an unfiltered observation that the audience should be cognitive of.

By all means, enjoy what you enjoy. You might totally disagree with this piece and have critiques, which is well within your right. But please, let’s have some nuance when discussing how class operates amongst Black folks in America.

This Week in History

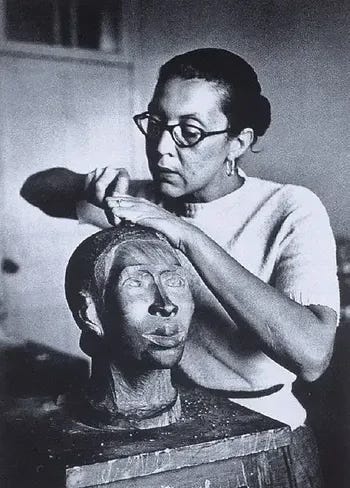

April 15, 1915: Elizabeth Catlett is born

A D.C. girl through and through, Catlett was born in the nation’s capital and graduated from Howard University. She gained acclaim as an innovative graphic artist and sculptor whose work reflected Black American women. She was a target of McCarthyism and was forced into exile in Mexico. Despite her ostracism, her work was displayed around the world.

April 15, 1990: In Living Color premieres

As the brainchild of Keenan Ivory Wayans, it was the unfiltered Black comedy show late night had been missing. The show solidified the Wayans as an entertainment dynasty and launched the careers of Jamie Foxx, Tommy Davidson, and Jim Carrey to name a few.

Music Momentos

April 15, 1995: “This Is How We Do It” reaches #1 on the Billboard Hot 100

A signature 90s party jam.

April 16, 2005: “Hate It or Love It” by the Game featuring 50 Cent reaches #1 on the Billboard Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart

A declaration for the Game’s generation of West Coast hip-hop.

April 17, 1990: Johnny Gill by Johnny Gill turns 35

By this point in Johnny’s career, he had released two solo albums, sang a string of duets with Stacy Lattisaw, and joined New Edition for a new shot of energy, but he finally had a chance to shine on his own with this album. Standouts include “Rub You the Right Way” and “My, My, My.”

April 19, 1980: “Don’t Say Goodnight (It’s Time For Love) (Parts 1 & 2)” by The Isley Brothers reaches #1 on the Billboard Hot Soul Singles chart

One of the many classics from the Isley-Jasper collaborative era.

April 21, 1990: “Ready or Not” by After 7 reaches #1 on the Billboard Hot Black Singles chart

Babyface and L.A. Reid composed a love song for the ages, as this song is currently enjoying TikTok virality.

What Has Us Hyped This Week

April 18: Alex Isley releases WHEN

This will mark Alex’s first body of work since partnering with Warner Records.

April 18: Keri Hilson releases We Need to Talk

With her first studio album in almost 15 years, Keri is ready to reclaim her narrative.

Closing Thoughts

If you haven’t already, be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel! We cover moments in Black American history, as well as current events.

Check out our apparel line! Just in time for Juneteenth, we have a Black American heritage baseball tee. We would love for you to purchase here.

See you soon!

Love This!!! ❤️🔥